Thomas Piketty describes the importance of the capital / income ratio, β. “The capital/income ratio for a country as a whole tells is nothing about the inequalities within a country, but β does measure the overall importance of capital in a society, so analyzing this ratio is a necessary first step in the study of inequality.” (Page 51).

Note that income is measured in dollars (or euros) per year, while capital is measured in dollars. (As an economist would say, income is a “flow” while capital is a “stock.”)

In most of Europe, β is between 5 and 6 these days. It is a bit under 5 in the United States, and a bit over 6 in Japan and Italy. (We’ll see later in the book that this ratio is heavily influenced by population growth. Thus, the faster-growing United States has a lower ratio, while Italy and Japan have among the lowest birthrates.)

The First Fundamental Law of Capitalism: α = r × β

α is the share of the nation’s income that comes from capital (a.k.a. property), as opposed to from labor.

r is the average rate of return on capital.

β is the Capital / Income ratio.

“For example, in the wealthy countries around 2010, income from capital (profits, interests, dividends, rents, etc.) generally hovered around 30% of national income (α). With a capital/income ratio (β) on the order of 600 percent, this meant that the [average] rate of return on capital (r) was around 5 percent.” (Page 53)

As Thomas Piketty states, this is “a pure accounting identity,” meaning by definition it is true. You can plug in any two variables, and solve for the third. However, he points out that historically speaking, for at least the last few hundred years r usually has been hovering around 4% to 5%. “

In the novels of Jane Austen and Honore de Balzac, the fact that land (like government bonds) yields roughly 5 percent of the amount of capital invested (or, equivalently, that the value of capital corresponds to roughly twenty years of annual rent) is so taken for granted that it often goes unmentioned. Contemporary readers were well aware that it took capital on the order of 1 million francs to produce an annual rent of 50,000 francs. For nineteenth-century novelists and their readers, the relation between capital and annual rent was self-evident, and the two measuring scales used interchangeably, as if rent and capital were synonymous, or perfectly equivalent in two different languages.(Page 53)

For example, the erstwhile heartthrob Mr. Darcy from Jane Austin’s Pride and Prejudice, had an annual income of “over 10,000 pounds,” which meant his wealth was over 500,000 pounds.

Also, this identity can be used to analyze a business (to calculate the rate of return it gets on capital) as well as a country.

It’s worth noting that throughout the book, Thomas Piketty is already accounting for inflation. During the 19th Century there was essentially no inflation (in England and the United States at least), so 5% meant 5%. Today inflation is a few percent, so the average rate of return is 4%-to-5% above the inflation rate, on average. Of course, with averages, some assets do worse, others do better.

While the exact rate of return bounces around from year to year, if you assume that r usually hovers around 5%, the value of α = r × β becomes clear, as it simplifies to α = .05 β. Thus, the higher the capital/income ratio, the larger the fraction of all income that will go to capital, as opposed to going to labor.

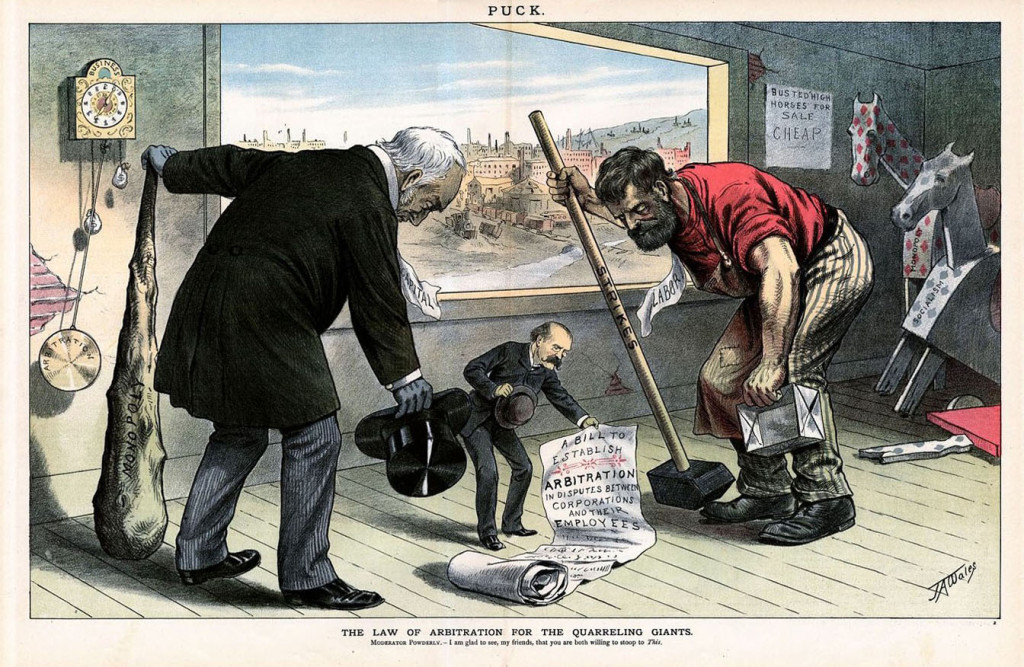

A cartoon from over a century ago which portrays capital and labor as intractable enemies. While a thriving economy needs both, there is an element of perpetual conflict as individuals attempt to maximize their income.